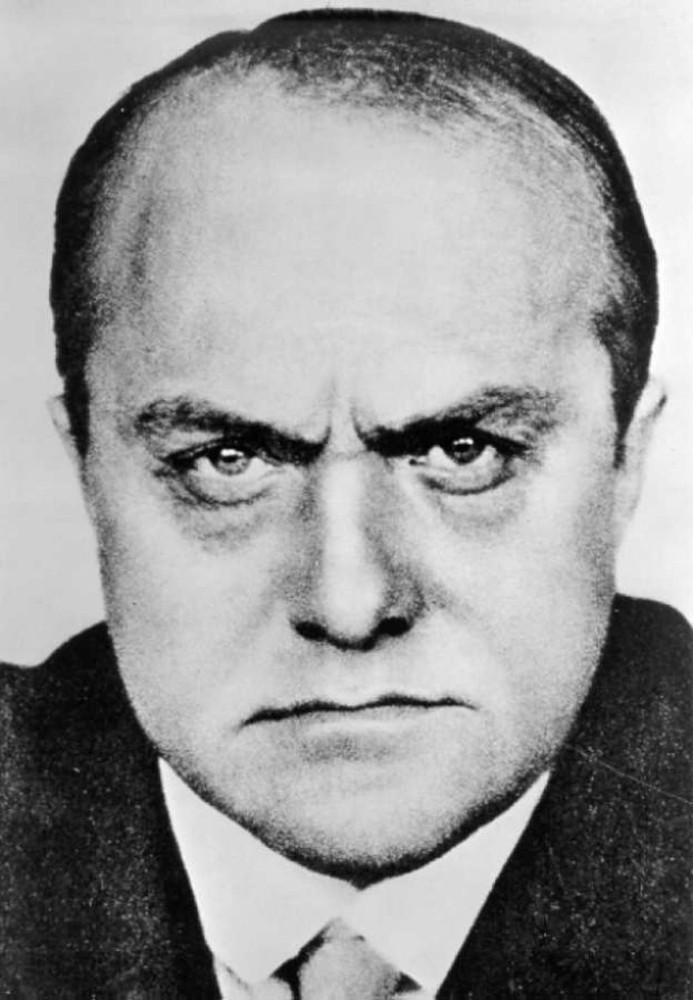

departure beckmann

In Beckmann’s own list of his works, the titles of the individual paintings of the triptych are: The Castle (left), The Staircase (right) and The Homecoming (middle painting).

All the paintings have the same height of 215.5cm, while the middle painting, at 115cm, is just a little wider than the side paintings at 99.5 cm each. Therefore the side paintings have considerable significance from the outset. They show bleak interiors with disturbing scenes, while in the middle painting we see the openness and breadth of the sea and the sky, and a royal family with their helpers on a bright, sunny day.

Established in 1942 by the American Society for Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism publishes current research articles, special issues, and timely book reviews in aesthetics and the arts. The term “aesthetics,” in this connection, is understood to include all studies of the arts and related types of experience from a philosophical, scientific, or other theoretical standpoint.

“The arts” are understood broadly to include not only traditional forms such as music, literature, theater, painting, architecture, sculpture, and dance, but also more recent additions such as film, photography, earthworks, performance art, as well as the crafts, decorative arts, digital and electronic production, and various aspects of popular culture.

The “moving wall” represents the time period between the last issue available in JSTOR and the most recently published issue of a journal. Moving walls are generally represented in years. In rare instances, a publisher has elected to have a “zero” moving wall, so their current issues are available in JSTOR shortly after publication.

Note: In calculating the moving wall, the current year is not counted.

For example, if the current year is 2008 and a journal has a 5 year moving wall, articles from the year 2002 are available.

Across Departure’s three panels, Beckmann juxtaposed images of restraint and release, aggression and refuge, contraction and openness. While the work is a triptych—a format traditionally used (in Christian altarpieces, for example) to convey an explicit narrative or meaning—Departure’s symbolic message remains ambiguous. Bound, mutilated, blindfolded, or clamping their eyes shut, the figures in the outer panels are victims of sadistic violence. However, their circumstances are uncertain; perhaps they are actors on a stage, accompanied at left by such incongruous props as a tilted still life and a crystal ball. In the center, passengers from another time—a king and queen with a child, a warrior figure, and a sailor—stand solemnly on a barge gliding on calm seas. The blue sky and net teeming with fish suggest good fortune.

Beckmann painted Departure in a time of mounting terror and uncertainty, as Adolf Hitler gained power in the artist’s native Germany. The painting was completed over several years, during which the artist was dismissed from his teaching position in Frankfurt and forced to move to Berlin, then to Amsterdam. The Nazi party had deemed Beckmann’s art “degenerate,” and he was among hundreds of artists whose work was censored for alleged immoral or anti-German qualities. While the painting is widely considered a biographical response to this period, Beckmann asserted a universal message: “Departure bears no tendentious meaning—it could well be applied to all times.”

![]()

Michael Trabitzsch widmet sich in seiner Dokumentation dem berühmten Maler Max Beckmann, den vor allem der Wahnsinn des Krieges maßgeblich bei der Schaffung seiner Meisterwerke beeinflusste. Seine zahlreichen Selbstporträts sind oft Ausdruck von starken menschlichen Gefühlen wie Eitelkeit, Zerknirschung, Lebenshunger und Todesangst. Oft ist er seiner Zeit voraus gewesen, wie beispielsweise mit dem Werk “Abschied”, in dem er die schweren Bedrohungen durch den Nationalsozialismus aufzeigt – obwohl es erst Anfang der 30er Jahre entstanden ist. Trabitzsch nähert sich diesem besonderen Künstler mittels bewegter Bilder, die teilweise auch an Originalschauplätzen entstanden sind. Zudem wurden Beckmanns private Tagebücher und Briefe genutzt, um ein umfassendes Porträt zu erschaffen.

Dokumentation , DE 2012

Filmverleih: Piffl Medien GmbH

FSK-Altersfreigabe: ab 6 Jahren

Kinostart (DE): 06.06.2013

Our writing can be punchy but we do our level best to ensure the material is accurate. If you believe we have made a mistake, please let us know.

That was when Beckmann thought up this highly disturbing triptych. On the left side there are people being tortured in all kinds of horrifying ways. On the right side, there is a woman who has a man tied upside down to her while she is ushered forward by a bell hop-looking guy. There is also someone, who should probably be helping this woman, playing the drums. And finally, in the middle is the peace scene, the scene that everyone wishes existed without the other two parts. It features four figures in a boat, one of which is a baby, departing for a better life. This is the hope that exists between scenes of terror. The artist said of this panel, “The King and Queen have freed themselves. The Queen carries the greatest treasure – Freedom – as her child in her lap. Freedom is the one thing that matters – it is the departure, the new start.” Beckmann insisted that this painting didn’t have a political message but he also hid the painting in his attic away from the Nazis and labeled the back of it, “Scenes from Shakespeare’s Tempest.” So that seems like a cover.

In Family Picture (1920), Beckmann alone represents consciousness, however wounded he is, and reduced to a helpless, inert child. The only man in a family of woman and children — in effect the father crippled and castrated by war (as the twisted horn he holds suggests) — he is conscious of the family’s miserable situation, and thus in a sense transcends it, however hurt. The work includes an allegory of the stages of life, represented by the three women around the table — one young and melancholy, one old and in complete despair, and the third reading the newspaper, indicating her interest in contemporary events, and thus her realism (in contrast to the two self-absorbed, indeed, self-pitying, unhappy women). Another sub-theme — so many of them involve women, who are usually, like the woman in the central panel of Departure, narcissistically remote and self-sufficient — is vanity, as the local Venus admiring herself in the mirror suggests. But her primping — she adjusts her hair — is futile, for no one else is likely to see her seductive beauty. The young men who might have appreciated it have died in the war, and her family is too indifferent to notice it. Her beauty is likely to be short-lived, as the dingy attic space suggests. She is another depressing part of the allegory of life. Note the light hanging from the ceiling in the center of the picture, like the light in Picasso’s Guernica, but here more clearly to the emotional point. For Picasso it was an ironic touch of realism in an abstract fantasy — very much like some of the realistic devices in his abstract Cubist paintings — while for Beckmann it is part of the banal reality of life, which is a nightmare come true.

But there is a deeper point to the Dadaistic realism of Höch and Heartfield: It suggests that the way to break the stalemate between abstraction and representation (more particularly, figuration) — the esthetic impasse created by their reconciliation — was a healthy nonconformist dose of outer-world influence, forcing a recalibration of their relationship in favor of representation, with abstraction going underground, as it were — not denied but hidden. The result was a sense that there was something magical about reality, that is, inherently fantastic and strange. What has been called “magical realism,” and I want to call “fantastic realism” — realism that calls attention to the absurdity of even the most matter-of-fact reality, that is, the bizarreness of the banal — became the major contribution of post-World War I German art to modern art. Weimar Germany was a bizarre world and Hitler was a bizarre character. The ideologues as well as the libertines of ’20s Berlin lived a fantasy, with equally disastrous social results.

To pass from either of these outer panels to the central one is to experience within this work that lessening of the force of Will that Schopenhauer found in the contemplation of beautiful things. Here the eye can pause and enjoy the pleasures of space and light. Here there is room to breathe. The king and his companions are departing from the world of Will, sailing away from unbounded cruelty and terror. While the people in the side panels are all imprisoned together, trapped in a dance of tormentor and tormented, the figures in the boat are more disengaged from one another, more complete as individuals–in a word, freer. The cords of desire that bind hands and bodies in the outer canvases are here transformed into ornamental jewelry: the king’s belt, the knight’s armbands, the woman’s bracelet and necklace. These people have slipped the bonds of Will, and we see the king in the process of relinquishing the objects of his desires: his left hand reaches behind him to release from his net a school of fish.

One possible key to the symbolic code of Departure may lie in the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. In the catalog of MOMA’s 2003 Beckmann retrospective, scholar Didier Ottinger tells us that the artist began reading Schopenhauer as a young man and that Beckmann’s “diary and correspondence testify to a real familiarity with the philosopher’s works.” 2 The core idea of Schopenhauer’s philosophy is stated in the title of his magnum opus, The World as Will and Representation. For Schopenhauer, the fundamental reality of the world and of all things, the thing-in-itself that we cannot perceive with our senses, is what he calls Will. This is a cruel, amoral, inhuman force that surges through and energizes the entire universe, causing creation and destruction, life and death, killing and reproduction. The best poetic evocation in English of Schopenhauerian Will is Dylan Thomas’s famous poem (written, coincidentally, about the same time that Beckmann was painting Departure):

References:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/425859

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/78367

http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=PdpA5umC538

http://www.sartle.com/artwork/departure-max-beckmann

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit6-1-06.asp

http://sites.google.com/site/beautyandterror/Home/triumph-over-the-will

http://www.masterworksfineart.com/educational-resources/andy-warhol/andy-warhols-details-of-renaissance-paintings-series-1984/